The past eighteen months have seen educational developers navigating the emergency closure of our campuses and a changed landscape in higher education due to the global Covid-19 pandemic. In this post, we suggest that the experience of these sudden changes to educational practice might be considered as a critical incident inspiring deep reflection. We suggest that tried and tested reflective frameworks for critical incident analysis are likely to be more useful than methodologies aligning with formally designed educational interventions.

We teach and co-ordinate academic professional development initiatives and programmes at TU Dublin, Ireland. Reflective practice has been the keystone of our work for more than 20 years. In common with similar formal and informal professional development activities familiar to members of SEDA, we have encouraged colleagues engaging with our programmes to use reflective writing as a means of “turning experience into knowledge” (McAlpine & Weston, 2000, p.364). SEDA mirrors this in its professional values, its Fellowship scheme, initiatives, and publications, most recently in the Special by Davis and Fitzpatrick (2019). Rich insights can arise from structured and deep reflection on practice, specifically on critical incidents in practice.

The “temporary online pivot” (Nordmann et al., 2020) triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic is generally agreed to be one of the most disruptive moments in higher education experienced for many decades. The real challenge now is in making sense of events since March 2020. Academics are trained to be critical and analytical, to explore phenomena and often, to introduce interventions, techniques or changes that might positively influence some aspect of our world or human experience. Much of this work takes on a formal structure or research design, planned over periods of time and approved by peers both before and after the work takes place. It is not a coincidence, then, that these highly developed skills of research and critical analysis have been applied to the changes we have experienced over the past eighteen months, and specifically to online learning and teaching.

However emergency remote teaching, most often using online platforms, is just that – an emergency measure. It has not been a planned educational intervention or initiative, it was not designed or peer-reviewed, it was not critically analysed by a research ethics committee or piloted in advance with small groups. Therefore, we suggest that usual modes of research and evaluation are not wholly appropriate and are unlikely to produce a complete picture or reliable interpretation to inform future practice.

A useful alternative exists by interpreting the events of the past year as a “critical incident” (Tripp, 1993). Critical incidents are important or striking problems or challenges from which we can extract in-depth learning. Normally, incidents are unexpected, unforeseen, and we are not prepared for them (for example, coping with difficult behaviour from a student in class). Practitioners will usually remember such incidents easily, discussing and writing about them as an important activity in their professional development. Through deep reflection they might identify actions, informed by evidence and literature, to resolve the challenges identified and lead to more positive outcomes in future.

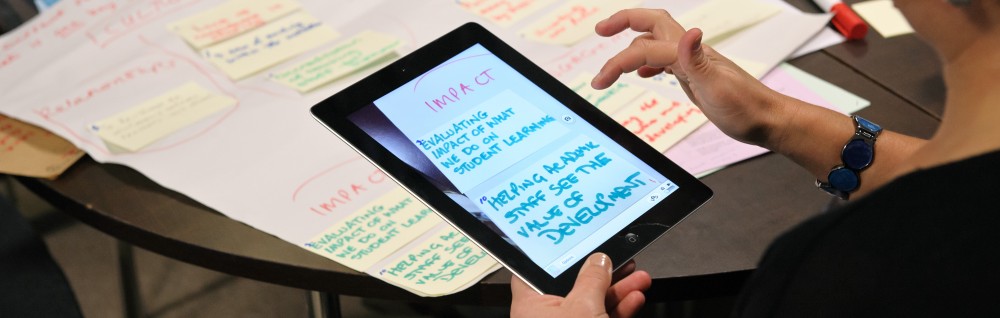

The process of analysis can call on existing well-known and valuable models of reflection and reflective writing such as that of Gibbs (1988) and Rolfe, Freshwater and Jasper (2001). Analysis usually involves description of the incident, documenting why it was striking or memorable and the immediate responses and feelings experienced. Critical reflection is then encouraged, that the person thinks about whether a personal mindset or expectation influenced or contributed to the incident, the contextual factors at play, the reasons why this episode might have occurred, and the perspectives of other people. Brookfield’s Four Lenses (1995) are valuable in building up the analysis – personal reflections, feedback from colleagues, feedback from students, and the literature, are all drawn upon to explore most fully what has happened and to validate planned actions for practice. We gather evidence to reflect and focus on what can be learned from the incident, how sense can be made of it, and what specific aspects of practice might be changed or enhanced to resolve at least some of the emerging issues. This might take a form similar to that outlined in Figure 1.

While our suggestions here may seem obvious, and reflection of this kind is habitual for many colleagues in SEDA, new or early career academics may not have experienced its very real benefits to their practice. Alternatively, analysing our experiences during the pandemic as a critical incident may seem like a bad fit, as the disruption has been on such a great scale: it is just too challenging compared with one small example from classroom practice. Studies and analyses of the pivot online and the experiences of students and staff are rapidly emerging: are these sufficient for such a watershed moment? We suggest that studies to date, while valuable, are not enough in themselves given the nature of the change. What we have experienced was not designed or planned to change teaching and learning in higher education. Multiple perspectives and reflection are needed to process this event. If we are considering the longer term, we need to interpret this evidence in short and meaningful bursts, and to support others in interpreting both the evidence and their own experiences of the past year to make sense of them and to identify appropriate actions.

Academic developers have a contribution to make here, particularly given our experience with using reflective practice and the kinds of lenses with which we are familiar. We have an opportunity to use this experience to enrich the process of coming to terms with the pandemic and informing – when and where we can – the future strategic directions for teaching and learning (inclusive of online learning) within our institutions.

Claire McAvinia, Muireann O’Keeffe, Roísín Donnelly, TU Dublin

References

Brookfield, S. (1995). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. San-Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Davis, C.L., & Fitzpatrick, M. (Eds.) (2019). Reflective Practice. SEDA Special 42

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Oxford: Further Education Unit, Oxford Brookes University.

McAlpine, L. & Weston, C. (2000). Reflection: Issues related to improving professors’ teaching and

students’ learning. Instructional Science 28, 363-385.

Nordmann, E., Horlin, C., Hutchison, J., Murray, J-A., Robson, L., Seery, M. & MacKay, J. (2020). 10 Simple Rules for Supporting a Temporary Online Pivot in Higher Education. PsyArXiv Preprints.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D. and Jasper, M. (2001). Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tripp, D. (1993). Critical Incidents in Teaching: Developing Professional Judgement. London: Routledge.

Thank you for this very valuable perspective.

A cycle of learning can start anywhere – here, about Covid, with very rapid and sometimes only barely planned action!

But, as you persuasively suggest, we can always learn – here about leaping online, but more broadly about responding to shock. About the resilience of our selves, our systems and processes, and how to increase resilience. Because Covid will not be the last shock.

I feel we’ll be better prepared to respond to shocks when our practices and our professional identity are rooted, not so much in particular techniques and methods, rather in (i) the values which underpin whatever our practice are and (ii) our understandings of the processes of learning.

As two modest offers on this – (i) of course the SEDA values, and (ii) Baume, D. &; Scanlon, E., 2018. What the research says about how and why learning happens. In Luckin, R, (Ed.) Enhancing Learning and Teaching with Technology – What the Research Says. London: UCL IoE Press, pp. 2–13.

Thank you again.

LikeLike

Pingback: CMALT Portfolio Review 2022 – the sustainable academic

Pingback: Learning from the lockdown.. | totallyrewired