I think it’s safe to say, we’ve probably all experienced the challenges around getting students to read in our academic environments, but has this been made worse since the pandemic? There’s a lot of assumptions in this area but little validation it seems.

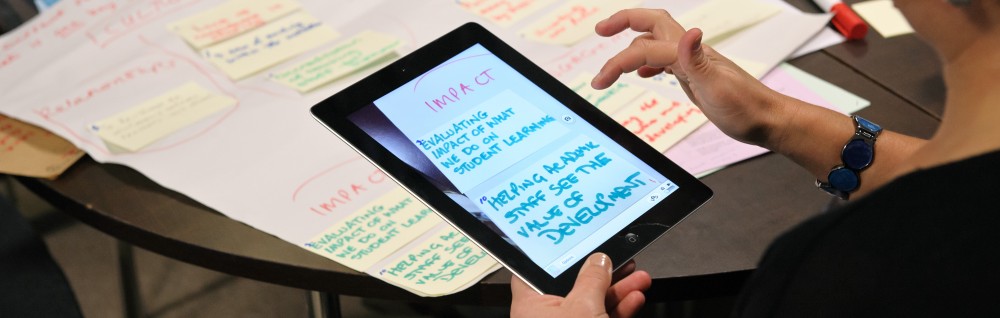

At a recent SEDA workshop looking into transitions into Higher Education, I posed a number of questions to the audience around the perception of digital reading practice. As part of the work we’re doing in this space as part of or QAA Collaborative Enhancement Project ‘Active Online Reading’, looking into students’ digital reading practice, we are seeking to better understand the problems students face, the barriers to academic reading, and the solutions that our students and academic community have used to overcome these barriers.

Below is a summary of the community’s contributions to this problem space.

Supporting students reading practice

Fundamentally, there’s still a feeling that many students’ just don’t prioritise reading as part of their studies. A number of reasons were given throughout this session, spreading from expectations that their degree wouldn’t involve reading (e.g. more creative courses), to anxieties around academic reading, or simply do not enjoy reading. It was generally felt that whilst we continue to ‘bang the drum’ on the importance of reading, perhaps we need to do more to evidence the value of academic reading?

Whilst reading skills support was offered at many institutions, how this was delivered varied dramatically, from not at all, to being academic led on single modules purely out of perceived need, to fully embedded and centrally delivered study skills sessions. However, questions were raised around how much we support ‘reading different resource types differently’. For example, reading a primary source will have a different goal and content to a newspaper, or blog post. Ensuring our students are thinking critically about the source, the goal, and the audience for the content is important, but do we do enough to educate our students on how to interpret these different sources of information, and how to synthesize across content?

The content and priority of institutional support was discussed. Many ‘reading skills’ sessions focussed primarily on skills like speed or skim reading primarily. Whilst important skills to develop, the academic community felt that priority should be focussed more on deep, critical reading practice. No examples were given of ‘deep reading’ sessions being facilitated beyond individual academic effort.

Finally, it was argued that academic literacy in general is still seen as a ‘bolt on’ in the main, rather than a core part of the learning experience, particularly at transitional points in the learning journey. Whilst examples were given where critical reading skills were covered in early years units, it was seen as the exception, not the norm, and often didn’t continue throughout the learning journey, just in first years.

Reading at Higher Education

A considerable talking point in this session was around student transitions to Higher Education and the approach to learning. A number of problems related to the significant shift expected from ‘directed learning’ to ‘critical thinkers’ that is often witnessed with new student cohorts. This relates back to academic literacy, but goes beyond that. We expect our students to be thinking critically about the subject matter, and drawing connections and conclusions from multiple sources we curate and they discover, yet this is a totally new skillset for many, and as evidenced previously, often under supported.

Having a better perspective on the different approaches to reading was seen as important here. Our expectations on the ‘volume of reading’ and the depth of reading that our students can (or will) deliver again, don’t always appear to align. Issues around setting unrealistic expectations and timescales were highlighted, especially when considering the whole course context (e.g. beyond a single module’s expectations). Critically, it was recognised that students read at different paces, digest, process, and synthesise information in different ways. Setting tight timelines on large or multiple sources for reading activity was seen as having negative implications, and should be restricted or avoided where possible. This was recognised as being particularly important for those who aren’t learning in their primary language.

Environments that our students read within were also considered . It was expressed that many students still don’t make time to read, or don’t make enough time to do core, let alone supplementary reading. It was also recognised that a growing problem relates to distraction. Finding the ‘right environment’ to foster good reading practice was seen as important, but we’re constantly distracted in the real world and in online environments. For digital reading spaces, it’s important to provide spaces that avoid distractions, notifications, and ‘noise’.

Digital reading obviously relies on technologies, for personal consumption, provided by institutions, and covering both software and hardware. Whilst many affordances come from digital reading, limitations in practice continue to proliferate.

Digital Literacies, and importantly, enabling good digital reading practice was again stressed. It was agreed that assumptions are often made around students’ digital skills, but the reality often doesn’t meet expectations, from key skills such as formatting text to reading in a digital space.

Alongside this, a number of affordances for academics were highlighted from digital tool use. Gaining insights into students behaviour, and through activities such as collaborative annotation, allowed academics to make more informed adjustments on cohort and individual mis/interpretations on the subject matter.

Conclusion

As a sector, it seems like we need to revisit, and reprioritise our support around developing digital reading practice. We need to ensure that we are covering the right skills that are required for good reading practice, rather than assuming there’s a one size fits all approach here. We need to be far more cognizant of the challenges, the barriers, and the anxieties around reading at higher education, and ensure that we are setting our students up to succeed in their reading practice early and as a priority, not ad-hoc and as a bolt on. Whilst digital literacy is being discussed across the sector regularly at present, developing students’ reading practice throughout academic studies still appears to be the exception, not the norm. Our research as part of the QAA Collaborative Enhancement Project ‘Active Online Reading’ will be seeking to identify and share good practice across the sector that encourages this activity, pulling together case studies of application, good practice from a skills based perspective, stories from staff and students, and academic literature. If you’d like to be kept up to date on this project, you can sign up for the mailing list here.

Matt East, Academic Lead at Talis

I write here as a life-long reader (and writer).

But, with the students currently joining higher education, maybe reading is the wrong place to start?

First – younger people have grown up learning in a far richer media environment than I did. They are multi-media-fluent in ways that baffle me (and which I envy). Maybe we need to adapt to this? Our reading-centric way isn’t universally right – it’s just a function of the world, the time, in which we grew up.

Second – maybe we could focus on using what’s read (or viewed or experienced or interacted with)? Maybe start, not with a text, but rather with questions and issues and problems. Then offer them a rich range of resources to explore to find and, better, construct their answers? (As soon as possible, get them asking their own questions and finding their own resources.) That would provide a point for the reading etc.

And third – encourage a critical approach to all the media they use. Get them doubting, interrogating, asking why and how and suchlike vital awkward questions.

Reading is a great tool for learning. It’s mine. But it’s not the only one.

LikeLike

Some really good points here David that I really agree with. Thanks for sharing your thoughts

LikeLike